2025 United Nations International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation: A Canadian Preview

by The Canadian Standing Committee, UN IYGP 2025

Background — The United Nations has declared 2025 as the International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation (IYGP) and March 21st as the World Day for Glaciers, to raise awareness of the critical role of glaciers, snow, and ice on local and global climate systems, and to recognize the social and economic impacts that changes will bring. The objectives of the IYGP are to better equip decision-makers and citizens around the world with the tools and information needed to address the consequences of the loss and changes of glaciers, snow and ice, and to ensure scientists and researchers have the capacity to provide relevant information to society. Achieving these goals requires global cooperation in research and synthesis efforts, actions that Canada is proud to contribute to.

Canadian Glaciers: Clear-Sky Composite Image for July 21-31, 2004.

United Nations resolutions are formal expressions of the opinion or will of United Nations members, and therefore the IYGP represents the desire of the international community to recognize the importance of glaciers to all of humanity. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) are leading the coordination of the IYGP, and an international conference dedicated to glaciers will be hosted by Tajikistan.

IYGP in Canada

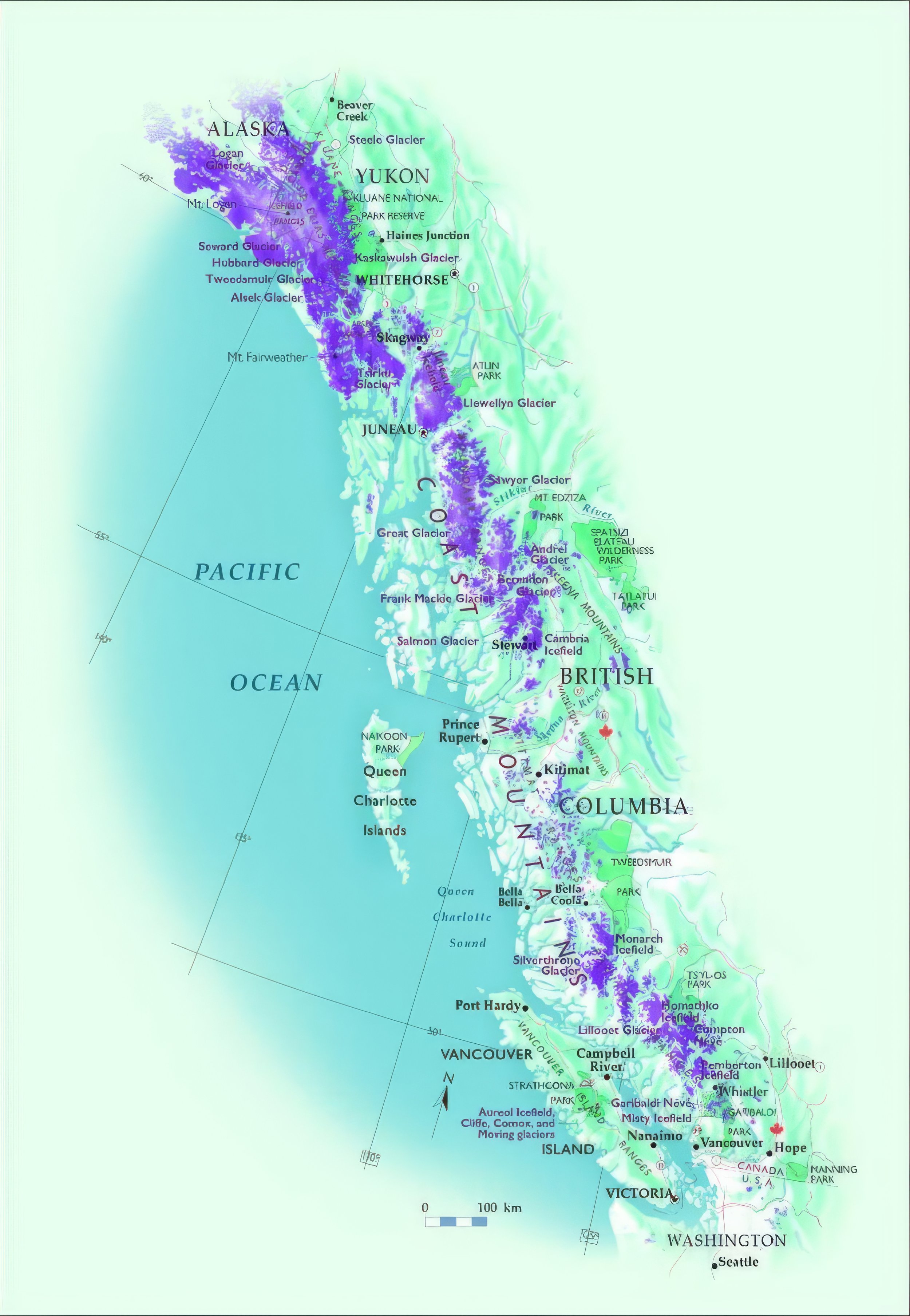

Snapshot in time: The glaciers of Canada, late-1990s. The areas shown in darker green are national parks and other protected areas; the areas shown in purple are glaciers. Modified from map in Canadian Geographic (Shilts and others, 1998; used with permission). Above: the glaciers of Canada’s Pacific Coast.

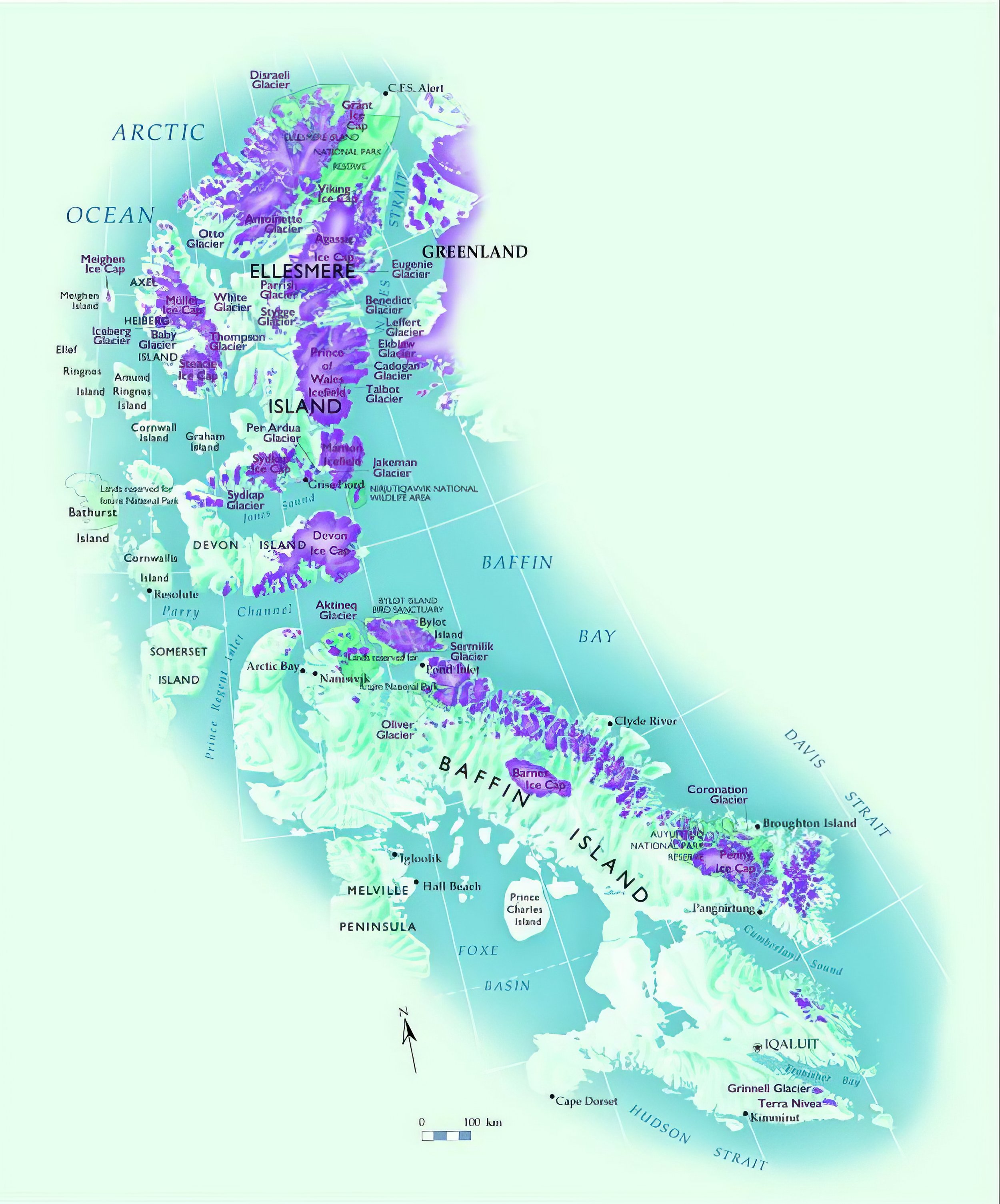

Glaciers are uniquely powerful in telling the story of climate change. For a long time, glaciers have been considered integral features of mountain landscapes, themselves remnants of the Earth’s environmental history. Their disappearance is a stark reminder of the impact humans are having on natural landscapes, and a stark harbinger of the environmental degradation still to come. Outside of the great ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica, Canada is the most glacierized country in the world, with approximately 50,000 square-kilometres of glacial ice laying over the western Cordillera, and another 150,000 square-kilometres laying over the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Since 1985, it has been estimated that approximately 1,140 glaciers have disappeared (as of 2020) in British Columbia and Alberta. This is an eight per cent decline and the loss of ice has accelerated significantly since 2011. These losses are due to changing conditions in both summer and winter, and glaciers across Canada’s western mountain ranges are projected to lose between 74% and 96% of their 2006 volumes by 2100. These changes will profoundly affect mountain hydrology, which is intimately linked to wildfires, floods, droughts, and the increasing frequency of other natural hazards. In Canada, the IYGP is about much more than glaciers; it is about Canadians’ relationship to the entire cryosphere, to water across all of its frozen forms, including glaciers, snow, ice, and permafrost. The IYGP will focus on freshwater impacts and changing hazards and risks in mountain and Arctic regions, but importantly, it will also provide an opportunity to celebrate frozen landscapes across the country.

The objectives for the IYGP in Canada are to:

- Raise awareness of:

the importance of all forms of snow and ice to Canada’s freshwater supplies and ecosystem functioning;

the hazards associated with changing snow and ice conditions in Canadian mountain and Arctic regions;

the local and downstream social, economic and cultural impacts of snow and ice change;

existing water management and cooperative frame-works and their role in finding solutions and adaptations to change

Promote Canadian snow and ice research, with the goal of improving our scientific understanding of climate change impacts on mountain and Arctic regions, and what these impacts mean for water-reliant natural and human systems.

- Improve scientific communication of snow and ice research findings.

The glaciers of arctic and eastern Canada.

- Foster recognition and appreciation for snow and ice as more than just “water resources,” with an emphasis on artistic and Indigenous perspectives.

- Promote policy improvement for water resources management in Canada at municipal, provincial and federal levels.

- Celebrate the beauty of our frozen lands, and the joy we have in experiencing them and sharing them with the world.

Success in the context of the Glacier Year requires improving our understanding of what an increasingly deglaciated and snow-free Canada will be like, and how we can adapt to the new circumstances of a warming world. More than climate action, we need to anticipate new and different needs in terms of infrastructure, hazard and emergency preparedness, economic policy, food security, energy security, tourism, and mountain living.

Observe - Predict - Protect

The glaciers of the Rocky and Columbia Mountains.

Understanding is integral to protection. Thanks to the dedicated work of Canadian researchers, government and academic institutions, there is already a solid foundation of science informing our understanding of the cryosphere. What we need now is to ensure that this scientific research continues and addresses new concerns. We rely upon the observations made by field scientists to make predictions and informed decisions, and when it comes to water-related policy making – whether in the mountains, in the prairies of Alberta or Saskatchewan, municipalities across the West, or beyond – good observations are a prerequisite to sound policy decisions. Every year, the state of our frozen water resources are changing, and committing to maintaining and improving scientific research will improve understanding of the situation. We cannot be effective water managers and decision-makers and citizens if we do not know and understand what is going on. We need to observe in order to predict the vulnerability of glaciers, snow and ice to climate change and their roles in regulating climate, ocean levels and preserving biodiversity.

Beyond IYGP

What do we mean by “preserve”? The greatest threat to glaciers is anthropogenic climate change and so glacial action means climate action. Glaciers are embedded in complex climate feedback systems already in flux, meaning that even if we stopped all CO 2 emissions today, there would still be a dramatic decline in glacial ice volumes in Canada. This means that while climate action is necessary, we also need to prepare for change. The purpose of calling for “glaciers’ preservation” is not really to “save the glaciers.” The purpose is to recognize the significance of water in its all of its frozen forms using glaciers as a symbol of the change to come. This will require a long-term commitment in Canada and around the world. In recognition of this, in August 2024 the UN General Assembly proclaimed a Decade of Action for Cryospheric Sciences, 2025–2034 to highlight the continuing need to understand melting glaciers and changes to the cryosphere by advancing related scientific research and monitoring and awareness of these critical environments.

For more information on Canada’s UN International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation, visit: www.unglacieryear.ca